THE 4TH PLATOON, 220TH AVIATION COMPANY:

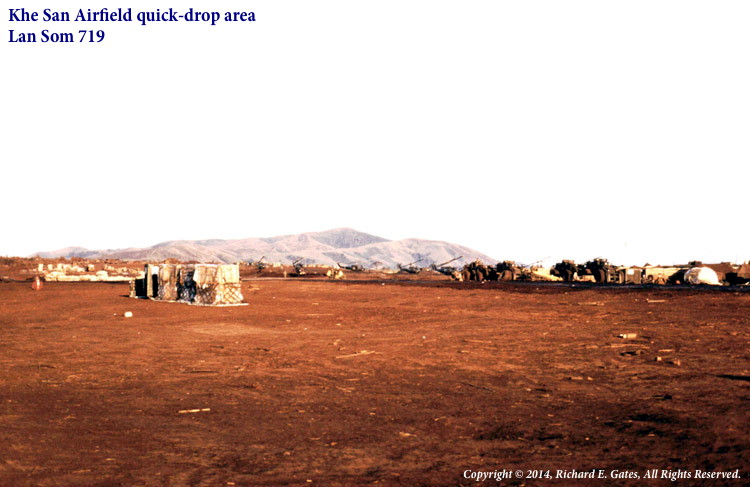

THE MEN AND THEIR MISSION,

OPERATION LAM SON 719, FEBRUARY 1971:

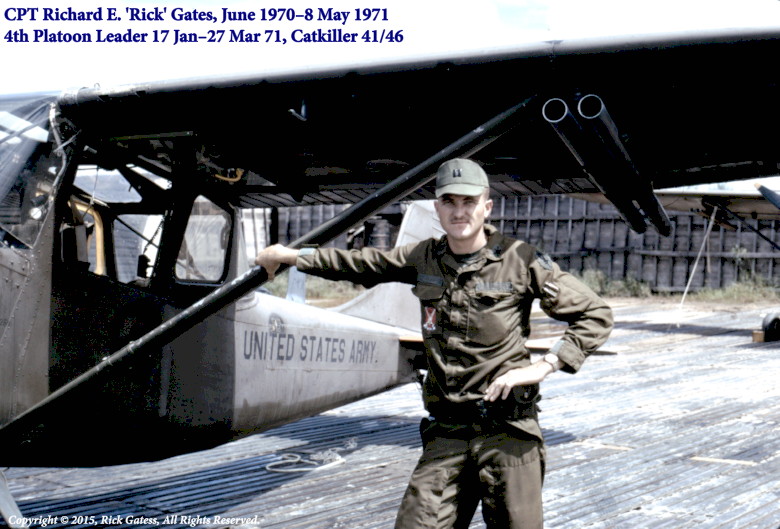

By Captain Richard E. ‘Rick’ Gates, 4th Platoon Commander

Transcribed and edited by Donald M. Ricks, Editor

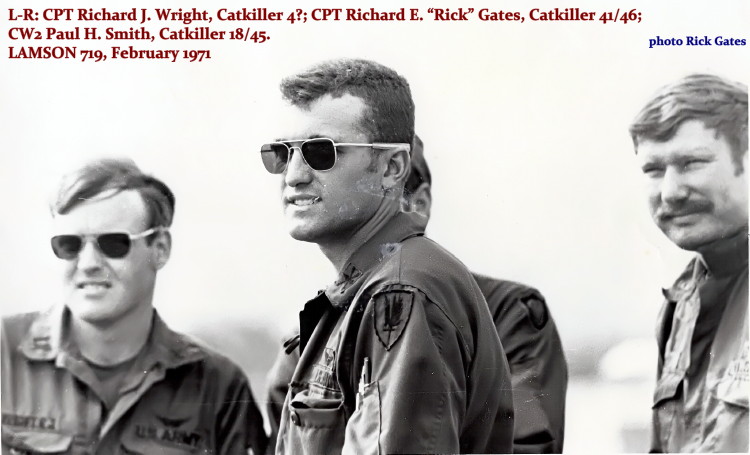

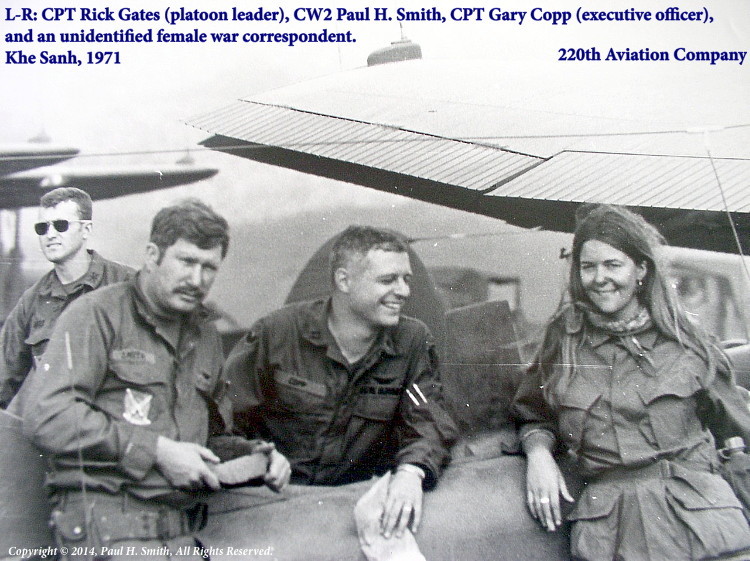

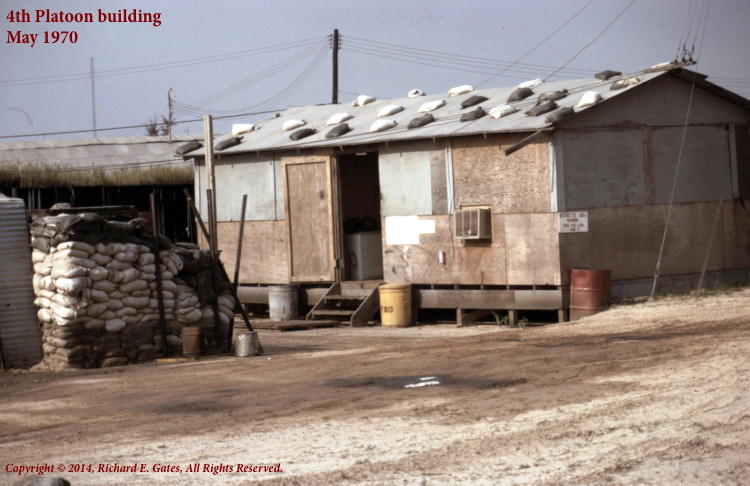

The 4th Platoon, 220th Aviation Company (Reconnaissance Airplane) was a normal TO&E platoon with no special attachments or extra troops assigned. During LAM SON 719, Captain (CPT) Rick Gates was the platoon commander. The First Flight Section Commander was CPT Richard J. Wright, with First Lieutenant (1LT) J. Soriano and WO1 John M. DeMots as pilots; and the Second Flight Section Commander was CPT Steve Chaplin, with CW2 Paul H. Smith and WO1 J. Zody as pilots. The Platoon Sergeant was Sergeant First Class (SFC) Rubin L. Oliver, with Specialist Fifth Class (SP5) Whitmore, SP5 Startz, Specialist Fourth Class (SP4) Montoya, SP4 Penrod, and SP4 Heller as Airplane Mechanics. These are the men who helped accomplish the mission as a team, and each, in my opinion, should be given equal credit for a job well done.

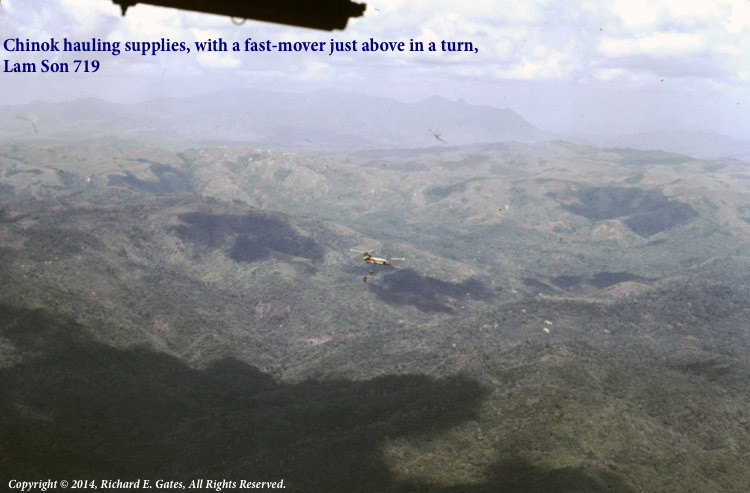

The 4th Platoon’s mission during LAM SON 719 was to fly in direct support of the 108th Artillery Group (Arty Gp), which was in direct artillery support of the 1st Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) Airborne Division and the 1st ARVN Infantry Division while deployed into Laos.

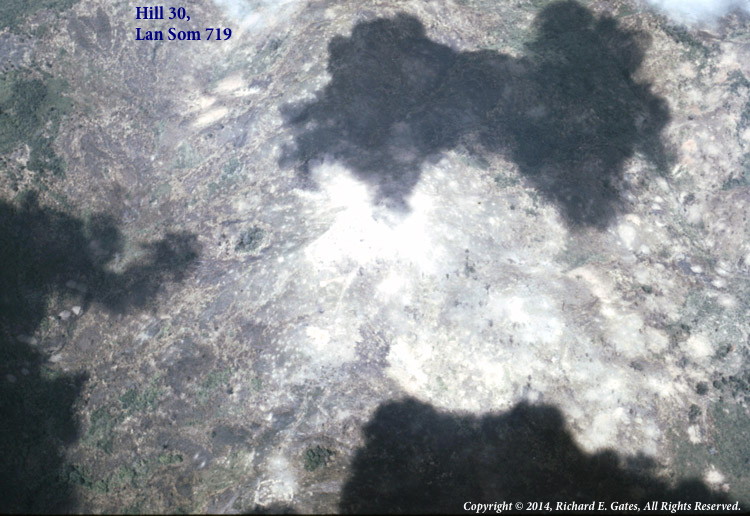

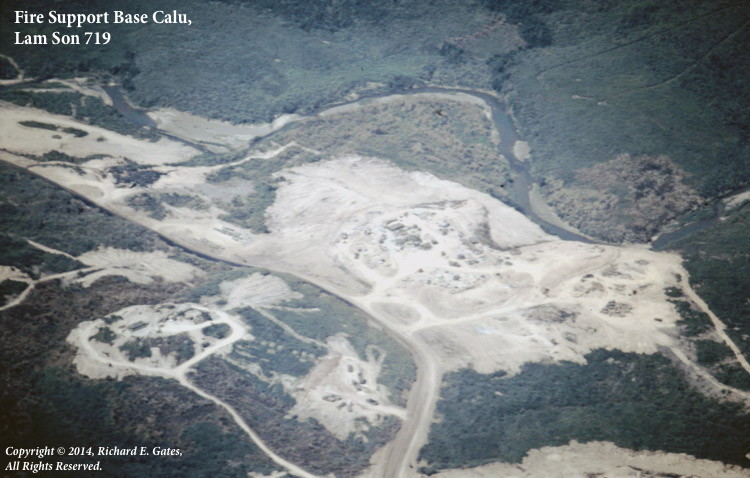

Our direct support to the 108th Arty Gp was to include: First, visual reconnaissance, which was to cover the area in which the South Vietnamese army was deployed—Laos. This was an extremely large area for one platoon of one airplane company to cover. We tried, and we did! We were also to recon the supply routes of the enemy forces. This of course included the Tri-Border area (the area where South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and Laos come together), well known for its high concentration of anti-aircraft artillery which guards one of the main infiltration routes of the Ho Chi Minh trail. The 4th Platoon was also expected to recon areas within South Vietnam when there was sufficient reason to believe the enemy was in close proximity to the firing batteries of the 108th Arty Gp.

Secondly, our direct support to the 108th Arty Gp included artillery (arty) adjustment. This included registering the firing batteries, arty adjustment on known or suspected enemy locations and/or equipment, as given by troops on the ground, and adjustments on targets found by us. These targets, in most cases, were the most successfully engaged—because they were fresh targets, targets that could be kept under observation until engaged and were targets that caught the enemy off guard. I might add that many of these type of targets were of enemy anti–aircraft weapons, who were in most cases shooting back as we adjusted–in our suppressive arty fires!

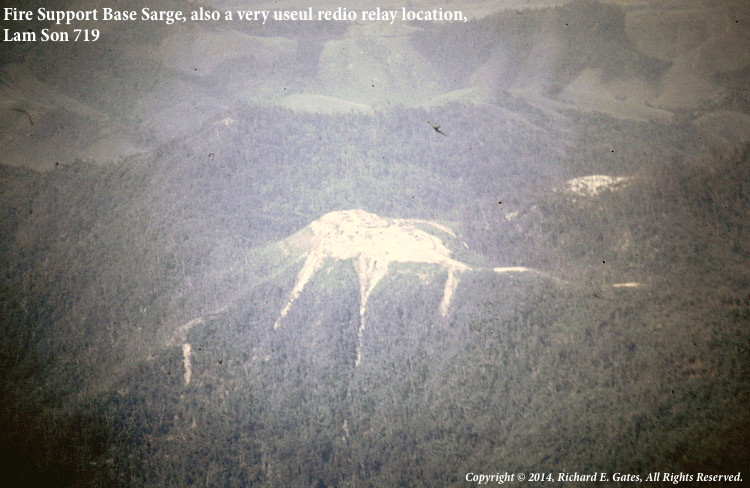

Thirdly, as the need and occasion arose, we conducted radio relay for the supported unit. In addition to supporting the 108th Arty Gp, on occasion, we also assisted the air force and armed army helicopter units in locating targets, directing air strikes, gun runs, and conducting target damage assessments.

The conditions under which we carried out our mission was trying most of the time. Our greatest hazard was the weather, mainly because our O–1 Birddogs were not equipped to fly under instrument conditions, it is susceptible to high crosswinds on landing and takeoff, and it is restricted from low altitude flight by regulations. The typical weather for the area of operation was: In early morning, covered with ground fog and/or Low ceilings with visibility between zero and two miles; late morning and during noon fairly clear; by the mid afternoon and early evening were periods of haze and smoke which reduced visibility to less than three miles. As you can imagine, our ability to accomplish the mission was often severely hampered by weather and which often reduced our effectiveness tremendously.

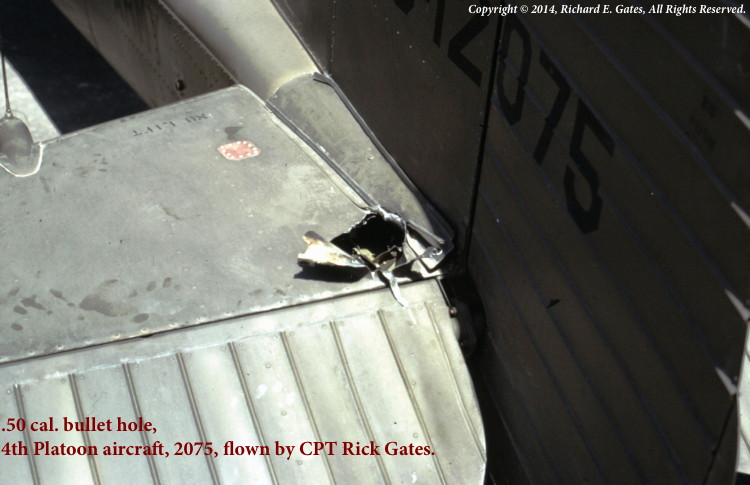

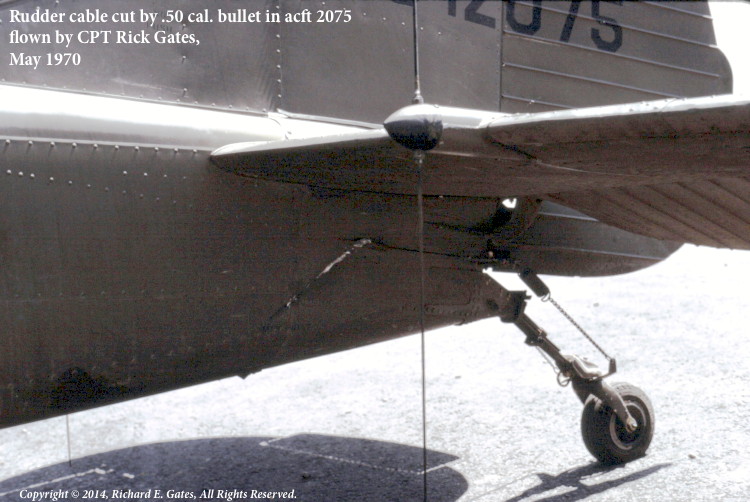

Our second main hazard, after we were able to get out into the area of operations, was, of course, the hostile fire. The O–1G Birddog is not an armed nor armored aircraft. It cannot return immediate suppressive fire; therefore, it is very susceptible to hostile fire. We generally tried to stay out of the effective range of small arms fire. However, we were constantly hampered by .51 caliber machine gun and anti–aircraft fire. This was especially so in the Tri–Borders area and around concentrations of enemy forces.

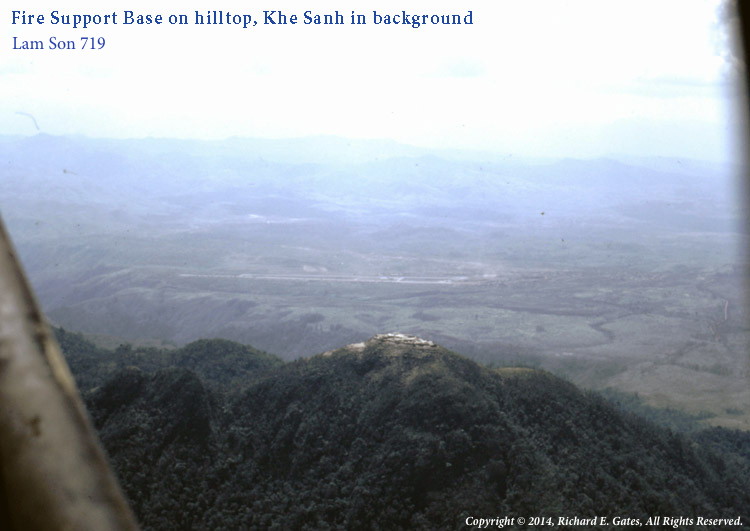

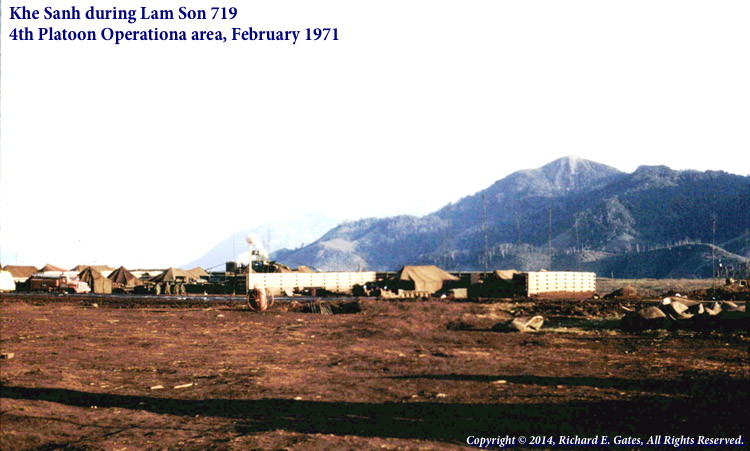

Our next main problem was maintenance. Wherever the equipment is, there also is the maintenance problem—and we had our share! I contribute the bulk of our maintenance issues not on our mechanics, who had to work under the severest conditions, but on the dust at Khe Sanh Air Strip. We had to change two complete engines due to excessive wear. That was 25% of our available 4th Platoon airplanes, and on top of that the only regular maintenance we did at Khe Sanh airstrip was refuel, add oil and change an occasional fouled spark plug. Another contributing factor to our maintenance problems was that we were required to employ our maintenance supervisor, the Platoon Sergeant, out at Khe Sanh airstrip 50% of the time instead of 100% back at Phu Bai, where all the main maintenance was performed. Also, our maintenance at Khe Sanh was hampered somewhat, especially toward the end of the operation, by incoming enemy mortar, rocket and artillery rounds. I must state, however, that our mechanics did a most outstanding job—that we never failed once in launching a mission because of our maintenance not being done!

And what were our results? Our results, the Fourth Platoon’s results, as far as we are concerned, are that we accomplished self–satisfaction in knowing that we tried and did our best with what we had. No, we are not satisfied with the number of KIAs, destroyed tanks, destroyed anti–aircraft weapons and etc. They are all just numbers, numbers that can be tallied from each of our mission debriefing forms. The reason we are not satisfied in terms of numbers is because these numbers do not equal the numbers the enemy had of each of these items. We wanted total victory and had to settle for much less in respect to the numbers. But we did not lose! We did not lose one pilot and we did not lose one airplane permanently. And we did gain, as stated before, self–satisfaction that we, the Fourth Platoon, worked as a team and that we did our best with what we had and it can never be said that we did not give our all!

EDITOR’S NOTE: A very good look into much of the action and obstacles facing the forces that participated in Lam Son 719 is at this site.

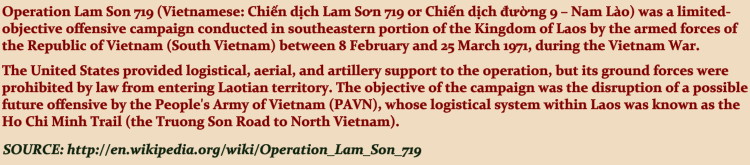

LAM SON 719 Photos, by Rick Gates:

There is an interesting story about FSB Sarge at this site: We Will Come Back for You.

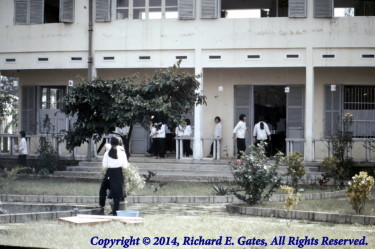

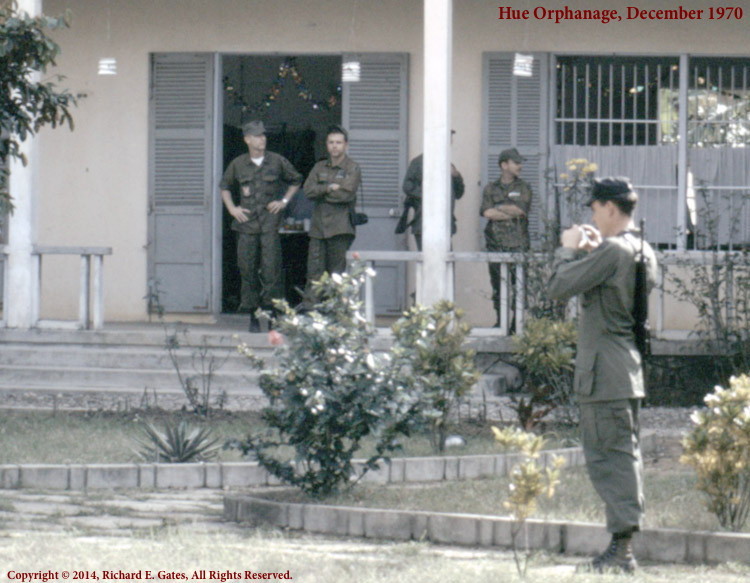

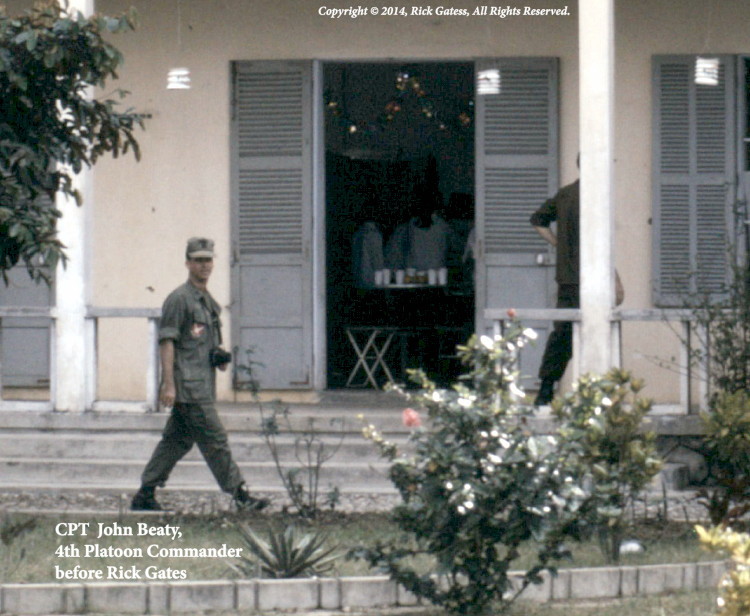

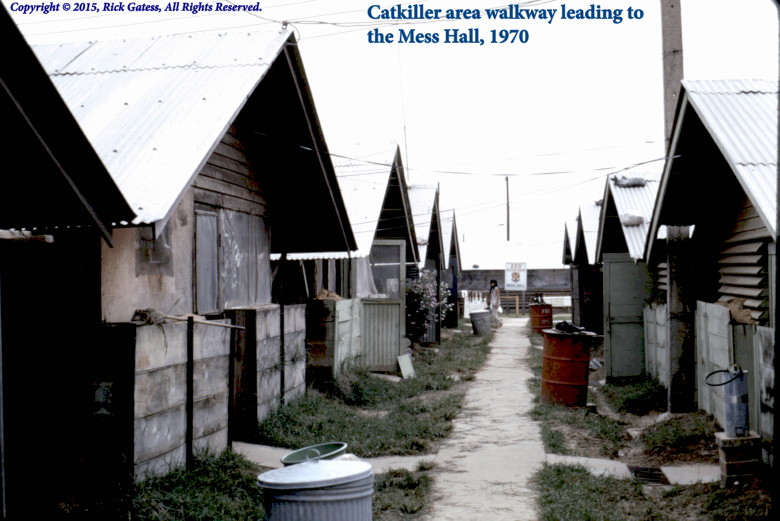

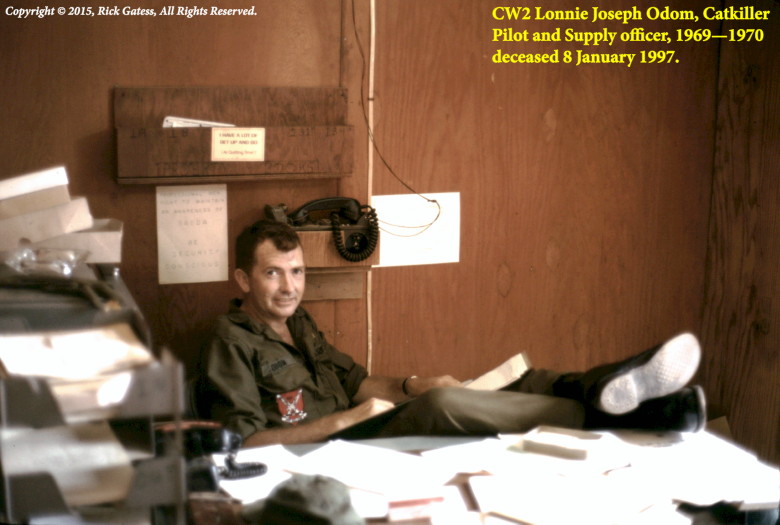

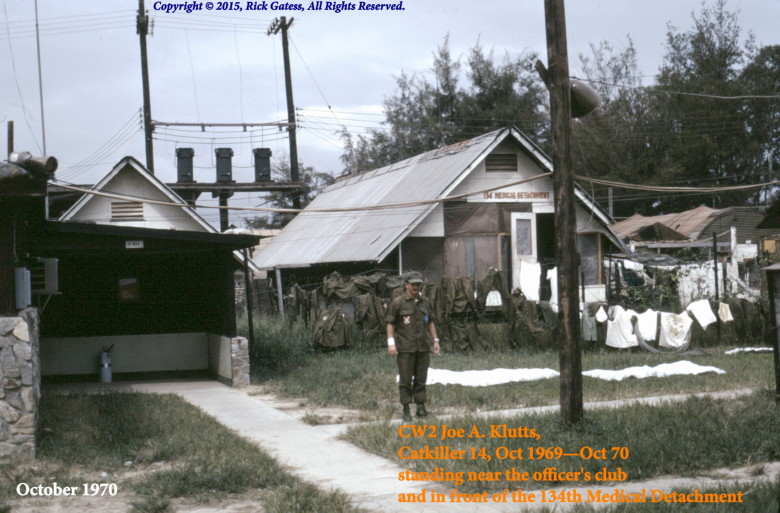

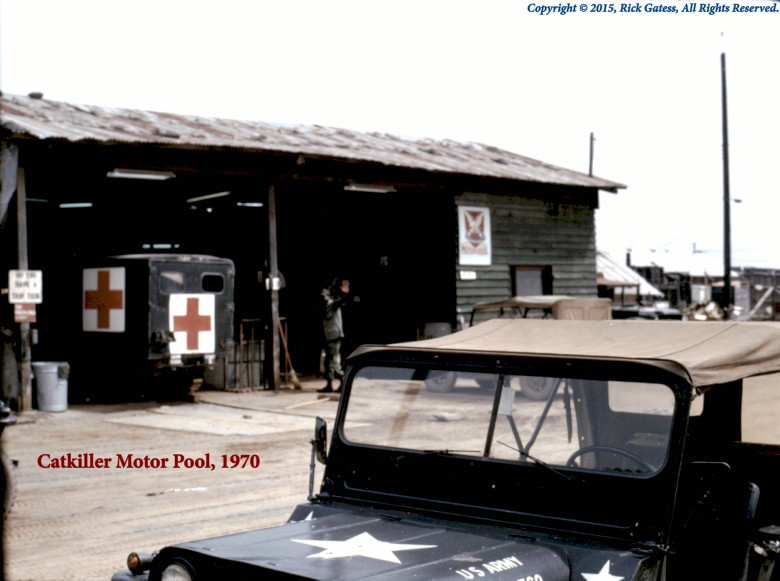

Other Photos by Rick Gates, 1970: (work in progress)

COMMENTS:

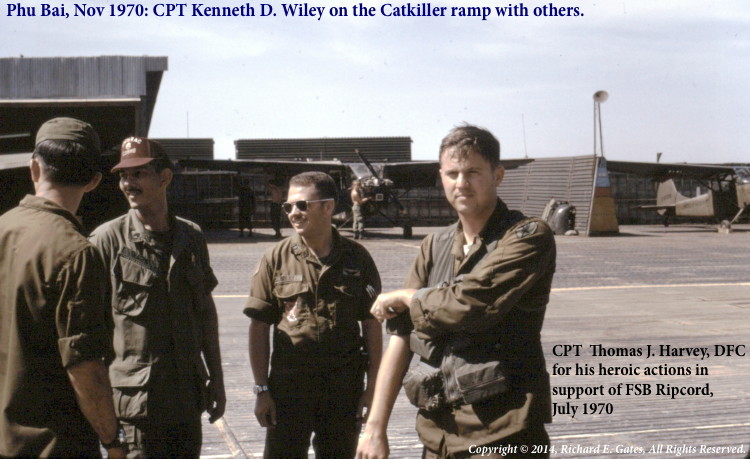

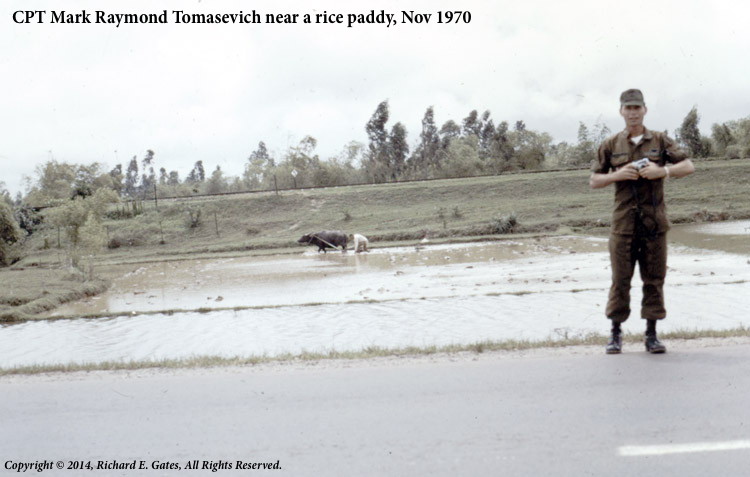

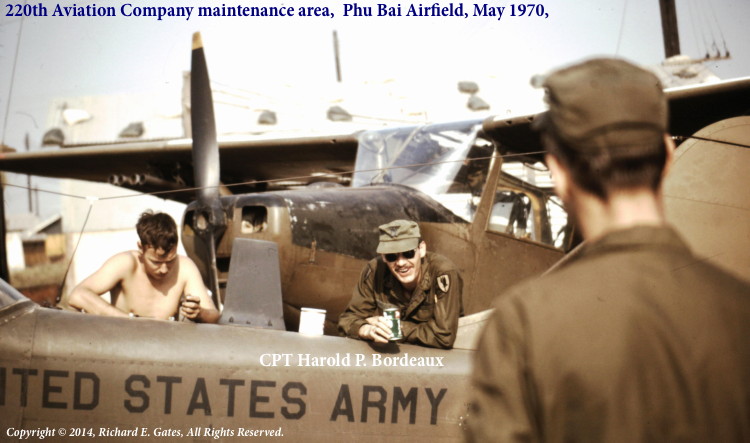

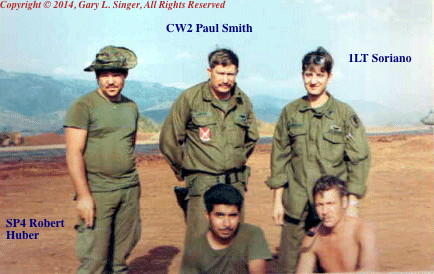

SP5 Gary L. Singer, Catkiller Crew Chief, May 1970–October 1971, sent in a few photographs that add to this era of Catkiller history:

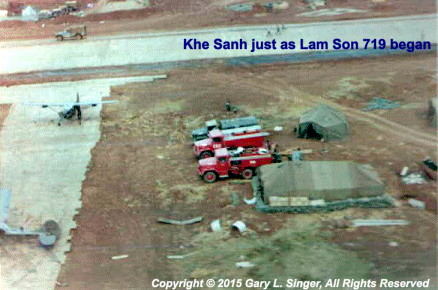

The top [photo] was taken at the start of Lam Son 719. They were moving in a lot of equipment and men in at that time. The only thing we had there was the round tent and a fuel truck (photo 2). They flew missions during the day, refueling at Khe Sahn, then the planes flew back to PhuBai at night at that time. After it really heated up the planes stayed at Khe sahn at night. I was back at PhuBai at that time. The man to the left was Sp4 Robert Huber (in our unit, he worked in the motor pool). He and I brought the fuel truck up there (full of avgas, was some ride) I can’t remember the officer to Mr. Smith’s [left], name. I remember the guys on the bottom but not their names. The one with the pipe came to PhuBai from an Otter company down south. I’m not in the picture, I was taking it. My tour was from May1970 to Oct.1971.

ADDTIONAL COMMENT BY PAUL SMITH:

The man on my left is Lt John Soriano (we call him Yosarrian from Catch 22) the other fellows must be crew chiefs as we seldom had observers at Khe Sanh. Every thing was bare before Lam Son 719 when we started the incursion and brought in a second runway, completed our bunker with a Mobile Air Traffic tower and GCA. The chief was my old classmate in air traffic school, CMSGT Bill Myers.